Just as the brain and body are connected, hands-on learning can also greatly influence social-emotional development. Experimenting with STEM tools like building blocks or robots doesn’t just helps kids build tech skills—it also enables them to work together and learn to not give up on challenging problems. When students’ heads, hearts, and hands are all engaged, holistic growth is much more likely to occur. And the social-emotional skills they develop from hands-on STEM activities prepare them to utilize resilience and emotional intelligence in the face of adversity, whether at school, at work, or in their personal lives.

Dr. Pam Davis, founder of the pop-up makerspace company called Wellbotics, knows this from personal experience. As a breast cancer survivor who experienced childhood pediatric medical trauma, Dr. Davis created Wellbotics to use STEAM experiences to support children facing trauma. The Wellbotics pop-up makerspace workshops help those affected by various traumas learn to develop stronger communication, problem-solving, and healthy coping skills for moving forward.

Eduporium’s team is also passionate about leveraging STEAM to increase social-emotional awareness in children, so I was delighted to speak to Dr. Davis about the philosophy behind Wellbotics and also her own approach to STEAM education. Besides SEL, we also discussed how social justice ties into technology, Dr. Davis's perspective as a Black female STEM leader, and the value of embodied learning experiences.

Tell me about your background in education and your history with robotics.

My background in education is long and broad. I have experience being on a Board of Education, and I’ve had experience with being a classroom teacher for 5th and 6th grade STEM. I've also been a grad school teacher, and I got to teach for the NASA Endeavor STEM Teaching Certificate Project. Plus, I was also a classroom teacher in kindergarten for a short time.

I love learning; I love education. It’s all part of the same story. I was raised by educators and my brother’s an educator, so I think that has a lot to do with it. Both of my parents were college professors, and a lot of people in my family were classroom teachers and pastors. It’s a family trait.

After your years of teaching experience, what led you from the education field to robotics?

The real catalyst for me was receiving my breast cancer diagnosis. Being in rooms with other breast cancer survivors, a lot of these moms were very concerned about the way their children were processing having a parent battling cancer. I saw a fantastic opportunity to create a conversation for all those kids, to give them the opportunity to be curious about what was going on in their household.

I worked with a social worker to create a LEGO robot game about alopecia. Kids learned the physiology behind alopecia, but they also learned about the social-emotional connection to hair and hair loss. These kids had questions and ways to see the world that they weren’t sharing.

It's hard to play when your mother is losing her hair and taking medicine and people are whispering. These kids are like, “I understand something is not playful about this moment, but how should I tackle this?” That hands-on activity, that permission to play, that opportunity to fail and try again and then succeed—that all created incredible conversations and relationships that I thought we needed to replicate.

It must be so scary for those kids. And it must have been scary for you too, going through cancer.

I was a sick kid. I had my first seizure when I was 10 years old and had brain surgery at 20, so I had already lost my hair. My cancer diagnosis wasn’t until my 40s, so by that time, I was ready with some wigs. Cancer was less of a shock for me than it would have been had I never been in a hospital.

My childhood epilepsy diagnosis gave me the perspective of a kid experiencing trauma. Kids don’t really experience trauma the same way that adults would. Not to say that they’re not scared—they are. But it’s different than people project. They will find ways to make it work. It creates this opportunity for what the research calls resilience.

And that’s what led you to found Wellbotics.

We started in the cancer community by making games for kids. Then, adults saw us walking in with robots, and next thing you know, we did something with the men there. Other people who had cancer heard about us and asked why we were only working with cancer patients. So, we began looking into various additional traumas. How can robot games help people navigate specific traumas like cancer or housing instability?

We also developed interest in schools and kids who were having a rough time. We were lucky to find folks who were fluent in the social worker world and also ready to become fluent in robotics. Right now, we tend to work with smaller groups of 10 to 15. We’re scaling up to take on a larger capacity, but I don’t think we’ll ever get rid of our smaller, more intimate groups.

We work on specific kinds of social-emotional awareness and ways that the robot can also be analogous to the human condition. What can you learn from the robot? What can you learn from teaching the robot? And what can you learn about your own capacity to succeed, to fail, to change?

So, interactions between humans and robots have social-emotional implications. Can you say more about the connection between SEL and technology?

Some SEL frameworks, like teamwork and curiosity, are built into the kinds of thinking that are common in STEM. Algorithmic thinking, design thinking, and computational thinking all include some social-emotional language. Our team looks at this analogy between programming a robot and thinking in humans, and how humans control the behavior of a robot.

In interacting with the robot, the human gets a peek into their own humanity: “I’ve changed behavior on this robot by changing its thinking. How do I change my thinking?” It’s a hands-on embodied event. Once you have a physical kind of interactive, cognitive, embodied moment, it changes your neuroplasticity.

So much is digital—I’m having a digital meeting, I type my digital messages—people lack the embodied experience.

Even when I had to do talk therapy for my cancer, I chose a place that had yoga classes. The first place I went was the yoga class, and I didn’t say anything to anybody. I went to the yoga classes for a couple of weeks before I said any words because I don’t think words are the universal language. Moving and doing and creating reach farther.

I appreciate you saying that words are not the universal language. There are kids that have trouble talking or are nonverbal, and getting them to talk is not necessarily the goal.

I agree. Communicating is broader than talking, so I'd say that building communication with the child is the first step. I have experience with kids who won’t say things unless they need things. And they still need the connections. All of them do. The question is: Are you going to be there listening when someone needs the connection from you?

And STEAM experiences help develop that connection?

I see STEAM as a problem-solving paradigm. Children are natural problem solvers. How do you learn how to walk? That’s a problem. I’ve always been very interested in the aspect of cognition that leads to problem solving, and I think a great deal of the problem solving is embedded in curiosity. When these problems are framed in curiosity, the solutions are more fun and can be tailored to different populations.

When you look at different ways people think, innovation is where some people naturally land. You’ve got a kid who encounters a toaster and uses it for bread, and you’ve also got a kid who encounters a toaster and takes it apart to see what’s inside. Innovation is a natural opportunity for people to express themselves. We can leverage the relationship between robots and humans to create a social-emotional vehicle for any folks who think with their hands.

You mentioned your interest in cognition. Did that inform your research process for your PhD?

I was fascinated with the brain because of my own trauma from being an epileptic, but nobody wants an epileptic with a scalpel to their brain. For my PhD, I was at Teachers College at Columbia University. My doctorate is in instructional media and technology, but I have a background in teaching and education because of my fascination with cognition and thinking.

I looked at the ways that technology can help build not only neural networks, but also social networks. My research had to do with creating the opportunities for underrepresented individuals to become teachers. In order to do that, they brought me into their network and I had to keep a foot in their system’s network, then figure out a way to bring those two together.

I was also a follower of artificial intelligence because there’s a huge overlap with AI and neurology. I was an early fangirl. That was all because I couldn’t be a brain surgeon. I wasn’t going to satisfy my story that way. If [my epilepsy diagnosis] had happened to me later on, maybe I’d have been more disappointed, but I was just curious.

With your interest in neurology and AI, what do you think about current AI innovations, like ChatGPT?

Like most innovations, the potential for harm will always receive more media coverage than its potential for good. They're both there. What I’m more curious about is how AI can fill in the gaps in the ways that writing and language are barriers in people’s lives.

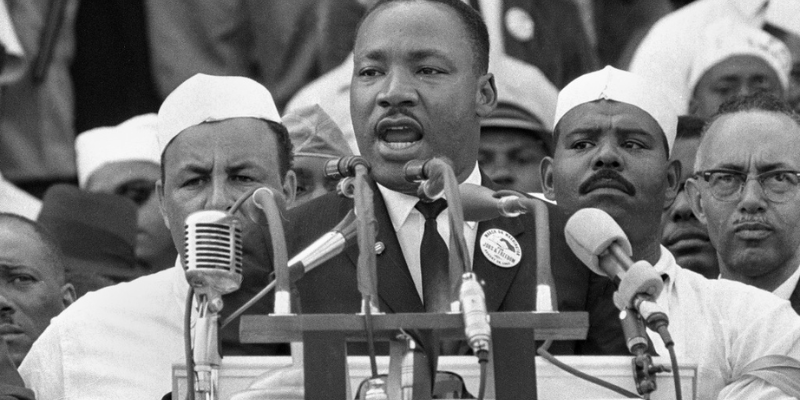

With all new technology, there’s social justice conversations that follow. Who is Dr. King without television? How does slavery get solved if there is no printing press? People say television represents the end of more nuanced communication, but television also created the only way Dr. King could have made his messages plain. And people didn’t want others to learn to read, but the printing press made it real hard to stop them. Because of that, the Booker T. [Washington]s and the Frederick Douglasses got to write.

All of that is technology. I am interested in where language is a barrier and how AI moves that area forward. How are folks using AI as a language interface to make inroads into worlds that have been closed to them?

I’d love to hear more of your thoughts on the intersection of social justice and technology.

This is where I live as a woman in my skin with a disability. If it wasn’t for the continued progress of certain technologies, certain opportunities wouldn’t happen. Everyone might get upset about social media at some point, for example. There is plenty to feel upset about, I recognize that. But there’s a corner of social media that has liberated, for instance, women, people who are heavier, and people with a certain texture of hair.

I think AI is the same. I’m a published writer. So, AI is a threat to what helps me to stand above the person who doesn’t know how to write. But what about that person who doesn’t know how to write? How can AI potentially help liberate them? What revolutionary opportunities do they all of a sudden have?

As you may know, Eduporium is one of few tech companies that is Black owned. How has being a Black woman in a tech environment affected your perspective?

In a lot of situations, I’ve been the only person of color, the only female, or the only educator on a panel or board. Some people say the first Black person or the first person to do something. I use the terminology of being "the only,” because it looks to the collective. Being "the first" sounds like there’s somebody coming after you, when there might not be.

One of the only ways to get invited to be “the only” is if what you’re offering up is excellent. You could have invited another white guy, but you invited me. Do they always hear what you’re saying? No, not always. But somebody really wanted to hear what I had to share. Maybe they’re not in the room with me, but somehow, somewhere, I made an impression.

What I’m enjoying witnessing is that the “onlies” are reaching new heights and getting to the point of being the deciders. I appreciate the role of the “only.” It’s really the only thing that creates the momentum to help broaden the field. The “onlies” are the ones who create rhythm, and it’s breathtaking to watch. I love it.

We appreciate Dr. Davis taking the time to talk with us, and we encourage you to check out the Wellbotics website for more on their trauma-informed robotics workshops. Plus, be sure you follow us on Twitter and Instagram to stay up to date with robotics news and learn more about how social justice and SEL each go along with STEAM learning.